by Marra PL. Lanot

Nick Joaquin came into Serafin Lanot’s life when Nick was just 17. Serafin at 21 years of age was then the literary editor of Manila Tribune in 1934. He was the first to publish Nick’s poem. I cannot remember what that poem was, but my father often cited “Six P.M.,” which ends with “conquistador tonight, clockpuncher tomorrow.” Serafin would also recite with relish and admiration excerpts of “The Innocence of Solomon,” with “Sheba, Sheba, open your eyes!/The apes defile your ivory temple…”

It seems my father forgot all about that brief encounter with the stripling Nick. Serafin never mentioned the incident even when Nick was already popular.

Maybe Serafin thought Nick might have no memory of his former literary editor. Serafin had been busy with his own life as a family man and taking care of Tamaraw, a small printing press and publishing house. Nick, meanwhile, focused on earning a living at the Philippine Free Press magazine and aiming for literary heights.

Fast forward to the 1960s and the 1970s. The Tamaraw Publishing House in Quezon City was the hub of activism. That is, students of the First Quarter Storm from the University of the Philippines Diliman to the Philippine College of Commerce on Lepanto sought the services of Tamaraw. Groups lie Kabataang Makabayan, and the soldiers from Clark Air Base in Angeles also had their anti-Vietnam War newsletter printed there. The U.P. Collegian needed to put out some 37,000 copies a week of the newspaper. Since the press, however, had only one offset and one linotype, the printing job didn’t materialize. Maybe students flocked to Tamaraw because the printing job were done for a song.

Meanwhile, in between the throbbing weekly articles in his inimitable, riveting style of new journalism, or literary journalism, Nick succumbed to the call of justice. He became a part of the union that went against the anti-labor practices at the Philippine Free Press. The editor-in-chief is Teodoro Locsin, Sr., then reportedly instigated a yellow union. In anger, Nick Joaquin and company resigned, and Nick never forgave Locsin after that.

The Jacintos of Jacinto Steel soon established the Asia-Philippines Leader magazine on Sta Mesa, and Nick served as editor-in-chief. Martial Law, however clamped its iron fist on media and forced practitioners out of job.

The unemployed Nick gathered his previously published profiles, reportage, other essays, plays, poems, and thus began his stream of book collections. Nora Aunor & Other Profiles, Ronnie Poe & Other Silhouettes, Reportage on Lovers, Reportage on Crime, Language of the Streets & Other Essays. Manila: Sin City & Other Chronicles. Quartet of the Tiger Moon: Scenes from the People Power Apocalypse. Pop Stories for Groovy Kids. Culture and History. Occasional Notes on Philippine Becoming. A Question of Heroes. And countless more. His Portrait of an Artist as Filipino, was filmed and staged restaged with various cast and directors.

Rewind. Mid-1960s. I was at the office of Nick Joaquin, the star reporter and literary editor of Philippine Free Press magazine. He was pounding his typewriter, copying his handwritten article. It was my first time to meet him in person. I handed him my poem, “Manila to Me,” and said I would leave it for him to read. “No, stay here while I read it. Suddenly he boomed, “Dahling, this is MY Manila.”

He looked at my byline and asked, “How are you related to Serafin Lanot?” I replied that he’s my father. “Wait for me, dahling, I’ll take you home. I haven’t seen my friend in ages!” I was surprised. He hailed a cab and took me home.

While going up the stairs, I called out my father. As soon as Nick saw my father, he blurted out, pointing at my father: “My discoverer!” I had no inkling as to what Nick was babbling about.

My father quipped: “Of course not! I’m not your discoverer! What am I, Christopher Columbus?!” And my father told the story of how he first met Nick. Nick as a teenager submitted his first poem for publication. Serafin was four years his senior. Serafin loved the poem and wondered if the name used was real or a pseudonym.

He asked around but nobody could tell him who the mysterious author was. So, Serafin asked the cashier to let him know when the poet would come to collect his fee so that he could meet Nick. It turned out the teener was working as a proofreader at the Manila Tribune. But as soon as Nick saw the approaching Serafin, Nick whizzed down the stairs and disappeared.

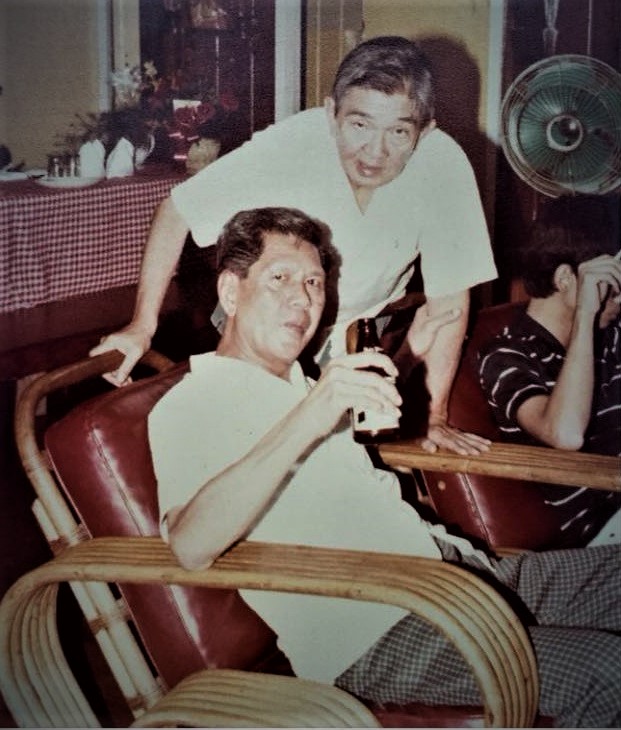

With that memory, the two writers became bosom buddies, beer or no beer. Serafin would learn little things from and about Nick, observe him up close, and both would giggle, chortle, and guffaw, as if in eternal banter.

Once, Nick wanted to write about Serafin and astrology. Nick played devil’s advocate, questioning the validity of astrology as a science, poking fun of it as mere fortune telling or superstition or sorcery, etc. Serafin remained cool throughout the long interview, and patiently explained everything.

When Nick’s article came out in Panorama magazine, not a trace of skepticism or cynicism would be gleaned. Soon, the open-minded Nick would smile and nod like a convert.

The two buddies, Nick Joaquin and Serafin Lanot, would remain friends until the end. Nick wouldn’t tire of visiting the house often, comfortably bringing his friends with him. He would bring along his friend Elena Roco, who engaged in a never-ending gossip with my Mom Gloria. Nick would bring Luis Taruc, Sammy Rodriguez, Alfredo Saulo and other Huks he knew Serafin knew. Nick would drag Recah Trinidad, Wilfrido Nolledo, Ninotchka Rosca, and other writers. He would listen to the Madrigal Singers on certain occasions, and meet my parents’ siblings. Nick was member of a boisterous family. The buddies would talk about Marcos, Macapagal, Ninoy, and Cory. The quiet Serafin and the booming Nick were interested in film, music, and the other arts.

When his friend left us, Nick stood quietly beside the window, and cried and cried. Both are now among the stars.