By Marra PL Lanot

At the launching of Serafin Lanot’s book, A New Look at Astrology through Fillipino Eyes. (L to R) Augusta Almedda, Ricky Lee, Odette Alcantara, Karina Bolasco.

Serafin Lanot was, is my father.

What can you say about someone you had been with for almost half a century? My father was shy and soft-spoken. He was a serious thinker, who loved to walk, play ping-pong, play the guitar, and sing kundimans and folk songs. He would win best dancer during barrio fiestas in Marinduque. He was a habitué of the kabaret somewhere not too far from Manila. He would swim the ocean, dog style. And he would explore hidden caves and rain forests, causing his mother, a schoolteacher, and his father, mayor of Boac, to worry. He loved riding his horse until he fell and bore a scar on his forehead for the rest of his life.

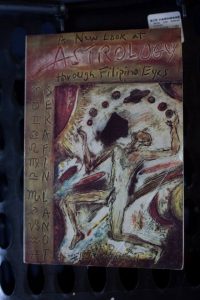

A New Look at Astrology through Filipino Eyes, the first major astrological book written in English that was published in the Philippines. Cover design by Danny Dalena.

In his book, A New Look at Astrology through Fillipino Eyes, his friend L. C. Poblador of Bulletin Today sums up Serafin Lanot’s childhood to adolescence thus: “bootblack, pan de sal peddler, copra carrier, sacristan, assistant road capataz.”

From adolescence to manhood, Serafin Lanot was “poetry editor, magazine editor, provincial board secretary, buy-and-sell entrepreneur, ghost writer, labor functionary, publisher, printer, Director of the Bureau of Printing.”

In Songs of the Brown Man, Lanot’s first collection of poetry, L.C. Poblador is even more specific. Poblador says of his friend: “Before he lived abroad, where he lived for four years, he traveled the breadth and length of the Philippines. He started earning his keep as poetry editor of the prewar Manila Tribune (now Manila Times); and became, successively assistant magazine editor of the same paper; provincial board secretary of Marinduque; bar and restaurant operator; magazine editor of the postwar Manila Chronicle; publicity man of the Municipal Symphony Orchestra of Manila that toured China, Japan, Hong Kong, Hawaii, and Guam; executive assistant of the Philippine Consulate in Chicago, Illinois; and now president-general manager of the Tamaraw Publishing Co., Inc. As a public-relations officer, he has promoted several successful projects, among them, the First Labor-Management Congress, the Philippine Association of Free Labor Unions (PAFLU), the public acceptance of the NARIC as a respectable institution in 1954-’55, and the Pan-Pacific Amity movement.”

After high school in Boac, he studied Law at the Manuel L. Quezon University, but dropped out. He later enrolled at the University of the Philippines for a Bachelor of Arts degree, but often beat his classes. Even without a degree, however, U.P. offered him a teaching job, but he declined, because he couldn’t imagine himself talking in front of students.

What my father never talked about was that he studied at the Columbia University in New York, where instead of writing a paper, his professors asked him to submit a compilation of his published works in the Philippines as journalist. He easily earned a diploma.

All these facts don’t really mean much unless one gets to understand the reasons for his choices in life.

As a teenager and as a bachelor, Papa always found a way to earn money. He didn’t want to ask his parents for money, and so he took on odd jobs. When he went to Manila after high school, he stayed with his cousins in Sampaloc. One day, he chanced upon the beautiful sound of piano playing coming from a big house from across the street. He wondered who the musician was. And then, he saw her, Gloria Vitug Licad, coming out of the house on her way to church. He was smitten. His cousins, all male, said my father wouldn’t even reach first base for she was wealthy and the father of the young woman was very, very strict. And he, my father, was poor. “Pustahan,” my father challenged them, “isang kaha ng sigarilyo, mapapasagotko ‘yan.” And the bet was on.

My father began visiting her in the house. My grandfather would sit between them, watching them like a dobermann. My Grandpa would spread a mat in front of them as a way of shooing my Papa away. Papa began to listen to classical music, read all the books he could on music until he could name a tune in just one bar. Mama was impressed.

Came Mama’s 18th birthday. She and her parents were surprised the debut was announced in the papers. Then, they found out that what they took for a jobless kanto boy was working for a newspaper. But that didn’t change my Lolo’s attitude toward my Papa. They were rich and my Papa was poor. It’s the telenovela theme of langit at lupa.

Well, to make the story short, my parents fell in love with each other, and nothing, not even the bet, which my mother found out and got mad about, could set them apart. Soon, they eloped. My Mom’s sister, her best friend, accompanied them to the civil wedding and went home with a letter from Mama, explaining to his father why she eloped and asking for forgiveness.

For a whole year, my Grandpa refused to speak to them. Until war broke out. The year before “Liberation,” my father took his wife and one-month-old baby (me) to Boac, Marinduque, by banca. War was raging, the sea was raging, and the sky was red. Papa went to his parents, thinking it was safer there than in Manila. My father loved his wife and daughter so much so that he didn’t join the Bataan Death March. My mother didn’t have breast milk, and she was bleeding for a year.

I was allergic to canned milk, goat’s milk, and cow’s milk. My father, tears streaming down his cheeks, carried me in his arms, looking for mothers who could spare his daughter breast milk. My father saw Japanese soldiers snatch babies, toss them in the air, and catch them with their bayonets. But when the Japs saw me, a tiny bundle of skin and bones, they would shake their heads and say, “She die, she die,” and leave me alone.

All along the hilly streets of Boac, mothers would call out to me and offer me their milk. Thanks to them, I survived.

When my Mom’s father learned he had a granddaughter, he asked my father to manage the wide expanse of plantation land in Lubao. My father declined. He would rather work hard on his own.

My father had wanted to take up Law because he was interested in justice. It was only when the Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon (HUKBALAHAP) personalities, led by Luis Taruc, Sammy Rodriguez, Alfredo Saulo, and Amado Hernandez, visited my father upon their release from prison that I found out that Papa knew them. “Ang daya ni Serafin,” they jested, “hindi nag-miyembro.” My father said he was never a joiner, but he helped in his own capacity as a sympathizer.

This explains why, in spite of his being part of management of the Manila Chronicle, he sided with the labor union. Also, before martial law, nationalists and activists, including Jose Ma. Sison, whom I had never personally met, would bring printing jobs to Tamaraw, due to the fast delivery, quality work, and low printing cost. When many of them were detained or went underground, the printing press never got paid.

Papa put up the nationalist newspaper, which was in Filipino, Ang Masa, with Ka Amado Hernandez as editor. Masa at that time referred to kneading bread. The newspaper Ang Masa referred to the broad masses of people. So, when Jose Burgos put out the Filipino counterpart of We Forum newspaper, he named it Ang Bagong Masa, because Ang Masa was still registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Papa wanted his children to meet his friends, and so he took us with him when he visited his friends like NMV Gonzalez, Franz Arcellana, Jose Lansang, Sr., Felipe de Leon, Sr., Leon O. Ty, Virgilio Reyes, Sr., Guillermo Tolentino, Botong Francisco, etc. We were also close to all our relatives.

Traveling to Quezon, Batangas, Cavite, Marinduque, Rizal, Zambales, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Tarlac, La Union, Baguio, etc., he would bring us along, in-laws and grandkids in tow. Once, he hired a jeepney to take us around the six towns of Marinduque in a day. He showed us the white beaches, and how uncorrupted by tourism his home province was. He told us how the moriones were done and why the festival was practised. We got to see the tradition of the putugan, how coconuts were harvested, and how lasses witnessed the harana, or serenade. He brought us to Lubao, where penitents during Holy Week flogged themselves, and where fiestas lit up with fireworks and Christmas with beautiful lanterns. We saw the salubong and the higante parade in Angono. We experienced shooting the rapids in Pagsangjan. He wanted us to know the Philippines.

When he was assigned as PR of the Municipal Symphony Orchestra of Manila that was scheduled to tour abroad, he accepted the job on condition that he could bring his wife and me with him. He believed traveling widened one’s perspective.

He also had his fix of pop culture. He enjoyed the komiks series of Bondying, TV shows of Dolphy and Panchito rendition of translated songs, Tang-tarang-tang, Pilita Corrales, Bonanza, Mission Impossible, The Avengers, The Saint, Superman, Supergirl, and others. Filipino movies weren’t foreign to his taste. He personally knew some actors like Rogelio de la Rosa, Lilia Dizon, Gil de Leon, Carlos Padilla, Patria Plata, Carmen Rosales, etc. In fact, when a labor union at Premier Productions split and formed People’s Pictures, Papa was invited to serve as PRO.

Serafin Lanot had a big, big heart for children and animals. He taught us how to be gentle with children and animals. He believed they were helpless and innocent. We learned from him the names of plants, flowers, and trees.

Papa regaled us with his stories and adventures during dinnertime. He admired Ho Chi Minh, Mahatma Gandhi, and Mao Tse Tung. He went to China with a group of Filipino journalists and businessmen in 1966. It was an “unofficial visit” as travel to the Iron Curtain was still banned. The Cultural Revolution was just starting, and the Chinese hosts often called on Papa to narrate what he saw when he was in China in 1949, which was just before the victory of Mao’s revolutionary forces. Papa told them that he witnessed prostitutes selling their wares in broad daylight, Chinese dying of hunger in the streets, and signs saying: “No dogs and Chinese allowed,” etc. The hosts would lead Papa to the limousine as if he was the head of delegation.

In London, Papa wanted to buy cashmere sweaters for me and Mama. When he asked about the cost, the snooty salesperson said: “That’s expensive,” to which Papa retorted, “I have money!” I secretly cringed with pity and anger. Papa always brought home the most representative pasalubong of the place he’d been to. From Paris, he brought back perfume and French bread. From Madrid, he bought veils. From Rome, he obtained rosaries blessed by the Pope. From Amsterdam, he gave me a huge repro of a Van Gogh Sunflowers. From Germany, he had frames of beautiful etchings. “If ever you go to Berlin,’ he said, make sure you go to East Berlin, “Ang ganda doon!” He would return home thin because he scrimped on his allowance just to buy us gifts.

After his first major stroke, Papa sold his printing press because none of his three children wanted to take over the business. He spent hours reading books, and went into esoteric studies. He read about palmistry, numerology, handwriting, dream interpretation, etc. Then he discovered the science, meaning. And usefulness of astrology in helping people with problems, personal or otherwise. He went into self-study, and passed the written examination given by astrological societies in the United States and the United Kingdom. He delved deeper in studies, closely seeking information from astronomers. Being keen on mathematics, without which one cannot draw an accurate astrological chart, Papa correctly made character readings and social, economic, and political predictions as well as warnings regarding accidents and disasters. He held workshops and trained those interested in astrology. He was invited to lecture abroad on his thoughts on reconciling Western and Eastern astrology. People from the left, center, and right gravitated to him and sought his help. He was willing to help those who were willing to listen and help others. He did all these for free.

In some of the workshops, he would appear with a pendant of plastic toys or whatever dangling around his neck like a voodoo amulet. His students would look at each other, sort of wondering if Papa was a credible astrologer. Soon, however, they would get enthralled by his teaching, which sounded like storytelling, and laughed when he cackled.

In his column, Cosmic Chatter in Manila Bulletin, he predicted that the “Cory magic,” a term he coined, would lead Cory Aquino to presidential victory. Towards his last years, he was racing to finish at least two books – the biography of Rizal and the birth of the Philippines as a nation, both naturally dealing with history, and, of course, from a Filipino astrologer’s viewpoint.

And so, Serafin Lanot reached full circle as he had always wanted to help others in his own quiet way, in the best way he knew. He was always ready to help anyone who sought his advice for a better, happier, peaceful, and meaningful life. He was open to new ideas, not minding if they were unpopular. In Serafin Lanot blended the scientific mind of an astrologer and the sensitivity of a poet.